Ryan McCorvie on The Science of Flavor: Why the Same Food Tastes Different to Everyone

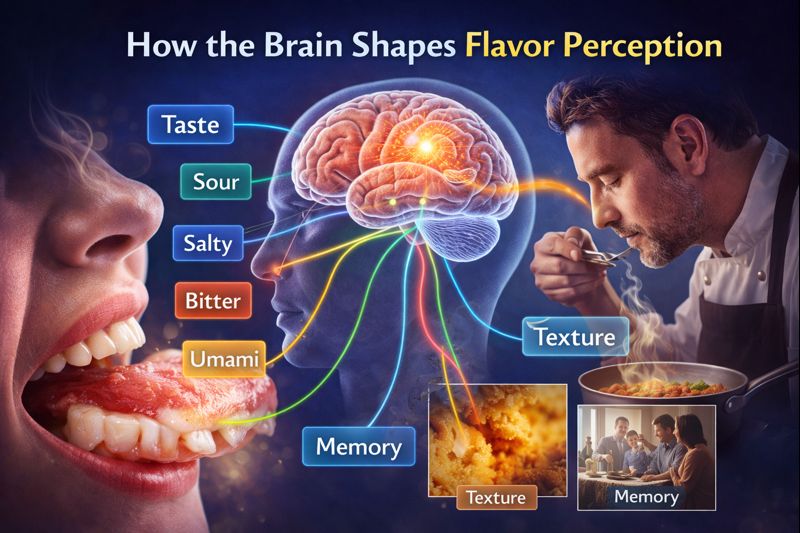

Two people can sit at the same table, take a bite of the same dish, and walk away with different impressions. This difference comes from the way the brain blends taste, smell, texture, and temperature into a single experience. Each sense contributes its own information, and the brain decides how to interpret it. Because no two people process these signals in the same way, flavor becomes personal.

Amateur chef Ryan McCorvie often focuses on subtle sensory cues in his visual work, and that same idea appears in how flavor perception forms. As he notes, “Flavor starts forming long before we taste anything. The brain pieces together tiny sensory signals and builds a complete impression in the background.” The brain collects small cues long before someone consciously identifies a taste, creating the foundation of each person’s individual experience.

The receptors on the tongue also play a part in shaping how food is perceived. These receptors respond to chemical compounds, and their sensitivity varies across individuals. A flavor that seems balanced to one person might strike someone else as strong or muted. These variations are small, yet they create noticeable differences in preference. They influence whether a person thinks a meal feels bold, mild, or somewhere in the middle.

Memory adds another layer to the experience. When someone tastes something familiar, the brain retrieves impressions tied to earlier moments. These stored impressions shape how new sensations are interpreted. Even when the dish is entirely new, the brain looks for something to compare it to. This constant search for familiarity shapes how people react to flavor and helps explain why personal opinions differ so widely.

Ryan McCorvie: Taste Isn’t Just Taste

Sweet and salty tastes tend to register quickly. The receptors that detect them respond to specific chemical signals with noticeable clarity.

“People often recognize these tastes with little effort because the brain is accustomed to sorting them out,” explains McCorvie. “When a dish highlights either one, the reaction forms almost immediately.”

Sour taste changes the feel of a dish by introducing sharpness or brightness. Some individuals enjoy this sensation because it adds liveliness, while others find it distracting. The receptors involved in detecting sour compounds respond in distinct patterns. These patterns influence how the brain balances sourness with other tastes and can shift overall perception.

Bitter taste is shaped by a wider range of receptors. These receptors recognize many different compounds, which creates a broad spectrum of sensations. Some people respond strongly to certain bitter signals and avoid foods that contain them. Others register bitterness as mild and may find it appealing. This variation helps explain why people disagree so often about dishes that contain noticeable bitter notes.

Umami introduces a sense of savoriness linked to specific chemical components. People who are more sensitive to these components tend to describe certain foods as rich or satisfying. Those who are less sensitive may not notice this depth as clearly. These differences influence how individuals react to savory flavors and how they describe the overall character of a meal.

Researchers continue exploring whether fat or starch should be considered additional tastes. Some findings point toward specialized receptors that respond to these components, while others suggest a more complex process. There is still debate, though many scientists believe taste perception may extend beyond the five familiar categories.

Smell: The Quiet Majority of Flavor

Aroma provides most of the information the brain uses to identify flavor. Researchers have found that between 75 and 95 percent of what people describe as taste actually comes from smell, according to a study published in Flavour. When food enters the mouth, small airborne compounds move toward the nose. Receptors inside the nasal passages detect these compounds and send signals that blend with taste information from the tongue. Without this process, many dishes would seem flat, even if the ingredients remained identical.

Smelling food before taking a bite only tells part of the story. Once chewing begins, warm air rises from the mouth and carries additional compounds toward the nose. This flow reveals aromas that were not apparent before eating. The experience shifts from a surface impression to a more complete picture. These internal signals shape much of what people perceive as flavor and often determine whether a dish feels balanced or unfinished.

Heat changes the structure of many chemical compounds in food. As ingredients warm, they release substances that produce distinct smells. These changes can be subtle or pronounced depending on the preparation. The transformation often determines how people interpret what they are eating. A dish that produces a fuller aroma tends to leave a stronger impression, even if the taste itself stays consistent.

“Some cooking methods trigger reactions that create complex aromatic compounds,” says McCorvie. “These reactions occur when certain molecules interact at higher temperatures.” The resulting aromas influence the character of cooked foods in noticeable ways. People respond to these signals with clarity because the smells carry information the brain sorts quickly. Aroma becomes a major factor in how the final flavor is judged.

Texture, Temperature, and the Physical Feel of Food

Texture influences how flavor is released and how satisfying a dish feels. A crisp bite sends different sensory signals than a smooth or creamy one. These sensations alter how ingredients break apart in the mouth and how quickly their flavors become noticeable. Consumer research shows that 44 percent of consumers are willing to pay more for foods with unusual textures, according to findings from NZMP. Preferences like these shape how people interpret the same ingredients and often guide which dishes they return to.

Temperature affects flavor by changing the behavior of both taste receptors and aromatic compounds. Warm dishes tend to release more aroma, which increases the overall intensity of flavor. Cooler dishes slow the release of these compounds and soften sharper elements. A dish served at an unexpected temperature can shift the entire impression, even if every ingredient stays the same.

Mouthfeel refers to the physical sensations created by compounds in the food. Fat coats the mouth in a way that feels soft or full. Certain components create a drying effect that changes how long flavors linger. Some ingredients produce warming or cooling sensations that stand apart from taste. These sensations work together with texture and temperature to shape how people interpret a dish.

The speed at which food dissolves also matters. Items that break down slowly release flavor at a measured pace. Foods that dissolve quickly deliver flavor in a single wave. This timing affects how the brain receives information and shapes the rhythm of eating. Some people prefer a slow unfolding, while others enjoy an immediate burst.

Memory, Culture, and Personal Bias

Flavor is strongly connected to memory. When someone eats a familiar food, the brain pulls forward earlier impressions that shape how new sensations are interpreted. These stored associations influence whether the person feels comfortable or hesitant toward a dish. A flavor linked to positive moments often feels warm, while one tied to a difficult memory may create resistance. These reactions form quietly and guide how individuals respond to small changes in taste.

“Cultural background influences how people learn to interpret flavor,” says McCorvie. “Individuals grow up with specific ingredients and preparation styles that become part of their routine.”

When they encounter something unfamiliar, their brains compare it with what they already know. Research examining how people respond to food cues found that brief exposure to certain features accounted for about 10 percent of the variation in how participants chose between appealing and healthy foods, according to a study published in Cognitive Research. These findings show how subtle cues can shape preference.

Personal bias plays a role as well. Some individuals enjoy strong, assertive flavors, while others lean toward milder profiles. These tendencies often form early and shift gradually over time. When people try new dishes, their reactions are shaped by these internal preferences. With repeated exposure, they may learn to appreciate tastes that once felt unfamiliar, although the process depends on their willingness to revisit those flavors.

Genetics introduces additional variation. Certain genes influence how strongly a person perceives bitterness, sweetness, or other sensations. Someone with heightened sensitivity might react sharply to specific compounds. Another person with lower sensitivity might barely notice them. These differences contribute to the wide range of reactions people have to the same foods.

Cooking With All Five Senses

Understanding how taste, smell, texture, temperature, and memory work together can make cooking feel more intuitive. When people pay attention to each sense, they begin to notice details that were easy to overlook. Small adjustments in one area can shift the entire experience of a dish. Even simple meals benefit from that attention.

Working with aroma can guide decisions during preparation. Observing how scents change with heat helps someone adjust timing or ingredient combinations. Paying attention to texture provides clues about how satisfying a dish will feel. Choosing whether something should be crisp, smooth, or tender changes how flavors unfold.

“Balancing taste becomes easier when each component is considered on its own,” says McCorvie. “A little more or less of a specific taste can alter the direction of a dish.” As someone becomes comfortable adjusting these elements, the process feels more natural. Choices become quicker and more confident as experience grows.

Personal history influences cooking as well. People often rely on familiar tastes, but trying new combinations gradually builds a broader sense of what works. These experiences create new memories that guide future decisions. Cooking becomes more flexible because the person gains a wider set of reference points.

When all these senses work together, flavor becomes easier to understand. Cooking shifts from following steps to paying attention to what the food communicates. With practice, this awareness helps create meals that reflect personal preference and a deeper understanding of how flavor comes together.